Could you imagine a world in which machines and algorithms have become so powerful, smart and precise, that they’re able to predict all your moves, fulfill all your desires, and recognize the slightest changes in your mood?

Could it be a world full of peace and harmony? All your wishes come true, all your prayers are answered? No need even to write to Santa anymore: with a blink of an eye he’s aware of your longings and hires Jeff Bezos and Amazon to make them all come true? No questions asked? No prayers, no dreams, no illusions?

Futurist, anthropologist and historian Yuval Noah Harari is less optimistic, describing the future of digital psychics. In his book Homo Deus, he depicts a society in which algorithms know more about your political preferences than you do and can predict the way you’ll vote, long before you have entered a voting station or even made up your mind.

How could that be? Small bits and details, fragments of conversation, the tiny digital footprints we leave behind daily, become our greatest curse as computer programs gather and deposit them, analyze and synthesize and draw up a digital blueprint of a you as a person, political animal, human. A map so detailed, so accurate, that even its existence will forever change the way our society functions.

Getting to know you is just one part of the game. Messing with your mind is the other. The smart combination of both these methods would end up in a brave new world Aldous Huxley and George Orwell could never have imagined, or known, to fear.

Some signs of this strange and dangerous world approaching are written on the wall, some signs are still camouflaged as innovation, designed and designated as serving humanity. Facebook was meant to fight our digital solitude, to build communities, to help us rediscover the joy of communication. The Internet was meant to cut distances, to connect people and help us cope with accelerating time. Journalism was meant to be a quest for truth, act as a social glue, not as a separator.

Why am I writing about this? On Tuesday, our last day in Los Angeles, we had a great opportunity to meet three experts at the University of Southern California and discuss with them several aspects of public opinion, polling and journalism.

Besides financial, socioeconomic and health-related polls, USC’s Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR) is known as one of the world’s leading engines of political polling, making headlines by predicting the victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential elections.

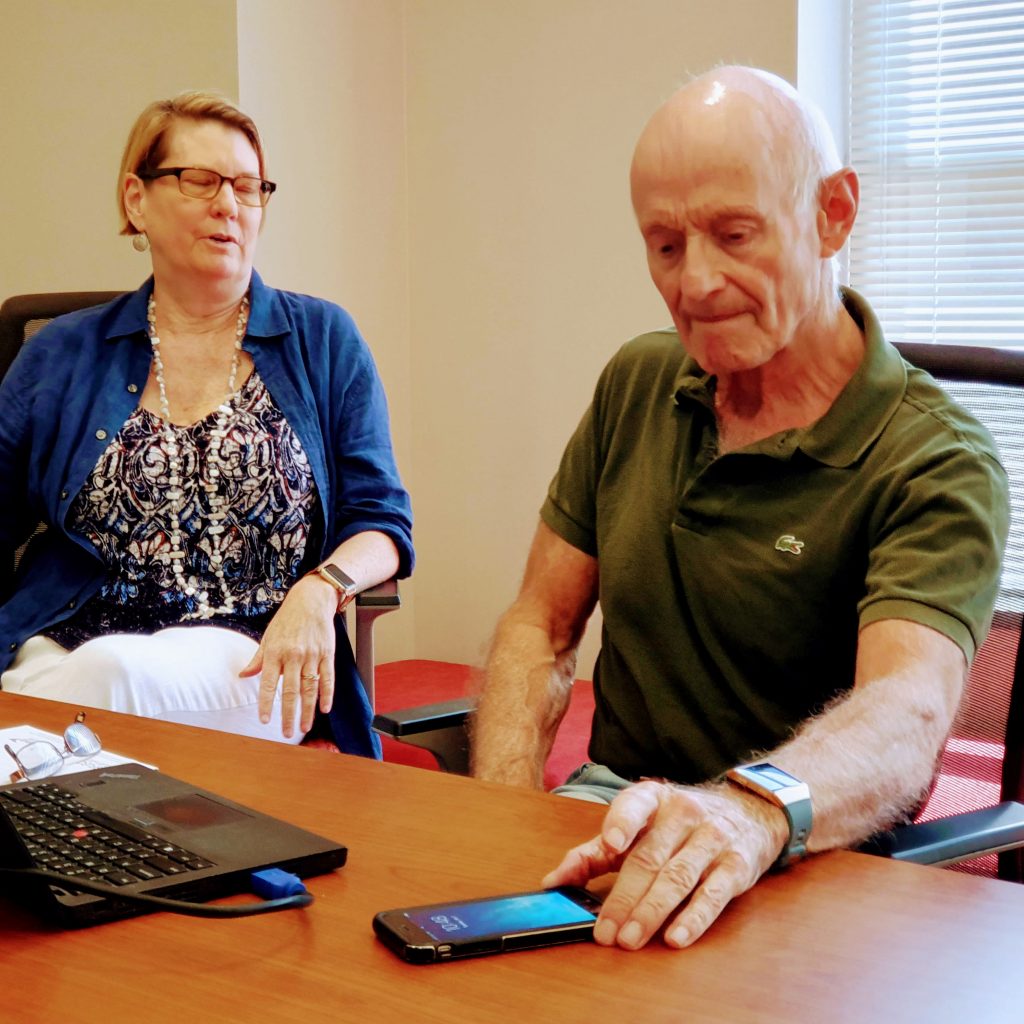

Jill Darling (survey director, but also a scholar who has intimate professional knowledge of journalism, since for twenty years she was associate director of the Los Angeles Times Poll, which conducted more than 400 surveys and earned multiple awards for their research), Arie Kapteyn (director of CESR and professor of Economics) and Robert Shrum (director of the Center for the Political Future) engaged SUSI scholars in an intriguing discussion. We covered how American politics has changed over the last 50 years, what role media has played in the rise of populism, the reasons behind media polarization and whether journalists can fight the temptation to report every populist PR trick some politicians are using to get media attention, just to name a few topics. And most importantly: what will happen in 2020?

“There’s no way Trump can win the election, but Democrats could lose the election,” said Robert Shrum quoting a friend. He explained how important it is to give the electorate a clear message of your positive vision. You cannot beat Trump just by pointing out how bad he is. People need convincing. People need clear messages. You need a clear overview of your supporters and your opponents, and you shouldn’t just rely on your gut feeling.

Mr. Shrum pointed out the dualistic role media have played during election campaigns. Media have openly opposed and criticized some candidates for their populist actions and statements spiced with dis- and misinformation, but still made a lot of money covering every controversial statement or action. Could journalists—at least for a while—use their right to remain silent? Could they give up juicy quotes, clickbait headlines and PR-actions?

To report, or not to report, that is the question.