The monsters are out.

They’re invisible. You don’t see them glancing out of dark windows at Taylor Place. Phoenix’s heat forces us to take shelter in our air-conditioned concrete cages. The windows are small. The locks are clicking. The doors are closed. We rarely talk to our neighbour. We smile politely, we chat, yes, but often just to be nice. We lock the door. We close the blinds. We wait for monsters to return. They can make our life a living hell.

“When I grew up, I stopped checking monsters under my bed and realized they’re inside my head,” says a muffled voice in a classroom. “It’s hard to be happy, when there’s a voice inside your head constantly screaming: you’re not good enough.“

Four students out of ten have experienced depression. Depression so strong it made their life miserable, as the study shows. Constant struggle with anxiety, desperation, loneliness and a lack of love has pushed some even further.

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune? Or to die, to sleep? Just end it all?

We don’t even know they’re crying for help.

Depression is not a flu. You cannot treat it with nice warm cup of tee, some pills and sleep. It grows its roots deep inside us, sucking out every last sparkle of life, joie de vivre, leaving an empty shell. A sense of worthlessness and fear of missing out prevents its victims from seeking help. Talking about depression seems to be even more humiliating.

Is there a way to help a depressed student?

Flickering screens around us, meant to bring us joy and bond us with our friends, have made it even more joyless. They google us silently, they buzz demandingly, and behind the screen a hungry Moloch yearns for likes and thumbs-up.

Britain scientists have found which social media platform causes the most mental problems. Sleep deprivation, fear of missing out, bullying, to name a few. Can we see Instagram as the root of evil, as the research shows? Is Youtube really doing better than others, bringing us knowledge, emotional support, sense of community and self-realization?

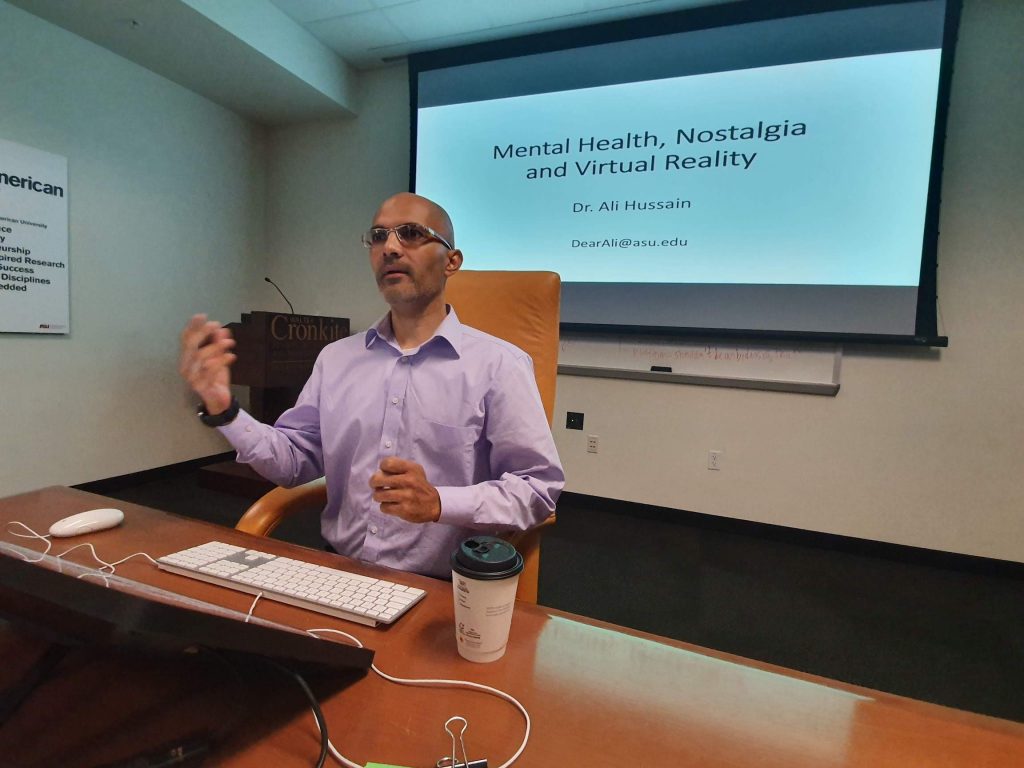

Two days ago, when I posted my first photo on Instagram – just a nice one of cactus in front of a high-rise building – I never thought about it. So meeting yesterday with Dr Ali Hussain changed it.

Ali’s trying to figure out how to use nostalgic memories to connect this miserable present with positive feelings of a past, and how to use technology and virtual reality to encourage victims of depression to open up, talk about their disease, as talking is the first step on the path of healing.

And as I learn during the discussion, he’s not alone. Specialists in South Africa are using hashtag stories to help rape victims. Portuguese and Spanish startups are teaming up to search for distress signals in Twitter feeds and offer psychological support for people crying for help.

So even hours later, as our team had a hopeless fight with iMacs in our computer lab, and as Dr. Mina Glenberg helped us to return to our childhood and catch virtual butterflies to feed the inhabitants of a virtual zoo, I was still thinking about the picture of a girl with many legs.