A few days ago, on June 14th, an overloaded ship capsized in the Mediterranean Sea. On the ship were more than 750 refugees. Only 104 refugees could be saved; 78 bodies were found dead. Around 500 people are still missing and at least 100 children were traveling on this ship to start a new life in another country. The Greek Coast Guard refused allegations that the ship capsized due to the Coast Guard attaching a tow rope to it. The incident has raised concerns about the safety of refugees attempting to cross the sea, and the UN has called for immediate action to prevent similar tragedies.

As a scholar coming from Turkey and with several publications on the representations of refugees in the media, I’m familiar with these tragic stories. According to UNHCR (2022), Turkey not only serves as a transit country for immigrants but also hosts the largest number of refugees, currently standing at 3.6 million people. During today’s discussions among SUSI scholars, it became apparent that all countries are grappling with similar kinds of refugee crises, in different contexts.

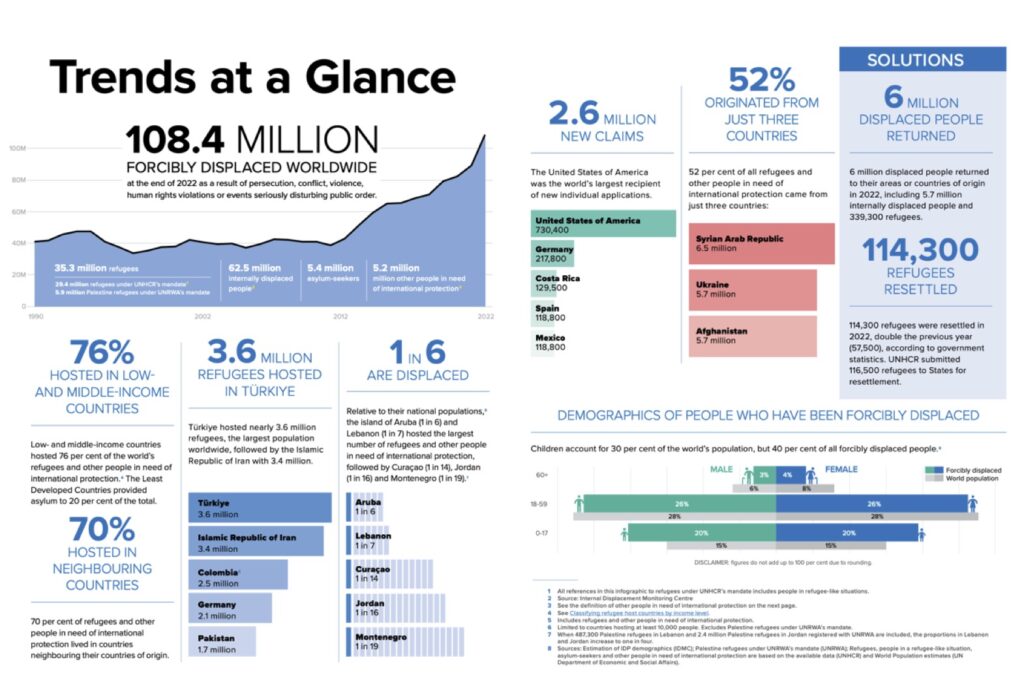

According to UNHCR (2022), 108.4 million around the world people have been displaced due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, or events seriously disturbing public order. “Displacement” might be the appropriate term to define the crisis that is often referred to as the “migration problem.” When analyzing UNHCR’s data, we observe varying numbers concerning different aspects. Turkey hosts the largest refugee population, whereas the U.S. is the world’s largest recipient of new individual applications, with Germany and Costa Rica following behind.

When comparing the data relative to each country’s population, it is noteworthy that Aruba hosts 1 in 6 refugees, while Lebanon hosts 1 in 7. Among all refugees, 52% are comprised of Syrians, Ukrainians, and Afghans. It can be concluded that war and internal conflicts serve as the primary drivers of displacement. However, it’s important to note that these numbers only represent registered displaced individuals. What about those who are irregular or undocumented?

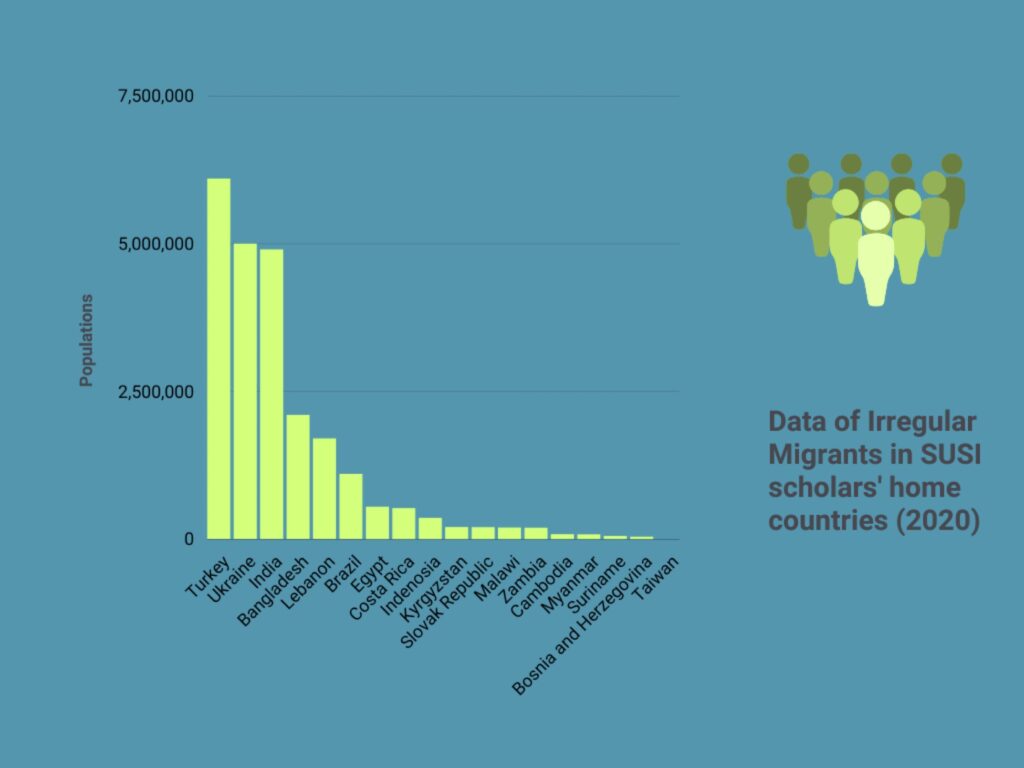

In migration studies, various terminologies have been used to define different issues related to immigration. In the comparative table below, we can observe the populations of irregular migrants in the home countries of SUSI scholars. This statistic is from 2020, prior to the Russian invasion in Ukraine. Before the war in Ukraine, the graph indicates that there were 5,000,000 irregular immigrants living in the country. However, when we analyze the updated data from UNHCR in 2022, we find that at least 5.7 million Ukrainians have left their country as refugees or irregular immigrants. These numbers demonstrate the devastating impact of wars.

Created by: Tirşe Erbaysal Filibeli

From the country with the smallest population to the largest, we observe that every country has an immigrant population. However, in this graph, the number of irregular immigrants in Taiwan is not available. Since it is defined as the “Taiwan province of China,” it is difficult to obtain separate statistics. Thanks to Shang Fang, we have discovered that there are at least 50,000 undocumented individuals living in Taiwan.[1]

When it comes to the U.S., migration becomes much more complicated.

Migration and Imaginary Borders

Citing political scientist Benedict Anderson’s theory of “imagined communities,” Dr. Rafael Martínez Orozco explained how nation-states construct borders. However, in the United States, particularly in certain areas, borders are more than just physical divisions; they are imaginary borders that pass through cities, separating Mexican-American people who once lived together, perhaps even as relatives and siblings. This separation has led to the construction of the Mexican Diaspora in the U.S., as people who stayed in the U.S. and those who stayed on the other side of the border experienced different paths. As Terry Greene-Sterling pointed out, over time, due to increasing crime rates and disappearances, Mexicans began attempting to cross the U.S. border. Unfortunately, many lost their lives due to dehydration and high temperatures. When I heard these tragic stories, I realized that in this part of the world, immigrants are not simply missing in the water, but they are missing in the desert.

The borderland of the U.S. is too complicated. This is why it can be difficult to comprehend, given the history of conflicts and disagreements within the country. However, as Rafael Martinez emphasized, it is crucial to establish connections between histories and cultures. By doing so, border narratives can be developed to evoke shared memories and experiences.

Though sharing her family’s history, Terry Greene Sterling was able to foster a sense of belonging among 18 scholars from various parts of the world. It is evident that people who have been displaced have a strong need to share their own stories. As scholars in the field of media and journalism, it is our responsibility to guide our students in reporting through creative and conflict-sensitive narratives.

Reporting on the border

While listening to the presentation by Ph.D. candidate Nisha Sridharan on reporting at the border, my focus was primarily on the aspect of “human-centric” reporting. During the writing of my own Ph.D. dissertation, I had the opportunity to attend an international conference in Prague where I presented a paper on people-oriented news versus leader-oriented news. According to Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Rouge (1965), “elite countries” and “elite people” still dominate the news, as they are considered newsworthy due to their elite status. Consequently, we often read news from the perspective of politicians, while human stories are overlooked.

Peace journalism critiques these “us versus them” perspectives and prioritizes “humanization” by giving voice to the voiceless. We must not forget the stories of mothers who search for their children’s bodies using their bare hands and sticks, and journalists should cover these stories. We must not forget the displacements and forced transformations faced by Indigenous Americans, and journalists should report on them. We must not forget the people who perish in the desert or at sea, and journalists report these stories. By teaching our students how to cover human stories and helping them understand why it is essential to do so, we can bring visibility to those who have suffered from wars, conflicts, oppressions, and any kind of human rights violation.

[1] For details please see, https://migrants-refugees.va/country-profile/taiwan/