It is well known among us, media scholars and journalists, that identities are constructed in relation to others. “My others” are the 17 different countries from SUSI Scholars and also the USA. So, in the past two weeks, I have never felt more Brazilian.

Being part of a program like SUSI involves engaging with a multitude of cultures, manners, accents, and unfortunately, stereotypes. Even though we try to avoid them, stereotypes inevitably surface as we explore the lives, universities, and daily routines of our colleagues from around the world.

This week, stereotypes were a significant part of my SUSI activities.

On Wednesday and Thursday, we spent time with Retha Hill (you can read about our adventures here!). One of the tasks she set for us was to create an art gallery using virtual reality to showcase our country’s history—a small slice of it. To construct my Brazilian gallery, I used Leonardo.ai to generate some AI images with prompts like “generate images of ordinary Brazilians.” The results were images of people wearing Indigenous headdresses in yellow and green (our flag colors) and shirtless men and women.

I was not surprised. These are common stereotypes about Brazilians, perpetuated even by our own media. It often seems like we are just samba, soccer, beaches, and tiny bikinis.

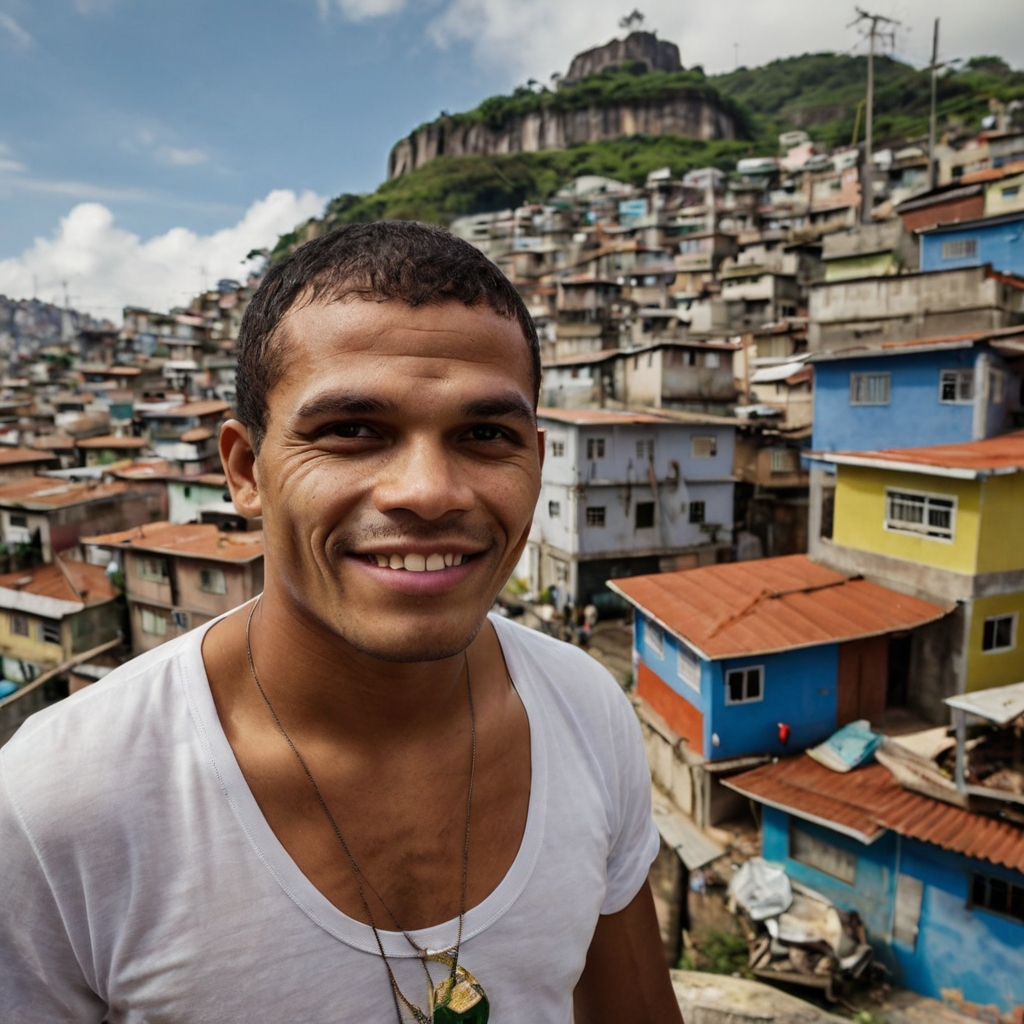

I then asked Leonardo.ai to generate “stereotypical images of Brazilian people,” and it produced pictures of very happy people living in favelas.

Again, not surprised. Favelas are informal urban settlements known for their precarious living conditions and limited access to essential services. Approximately 16.8 million people live in Brazil’s favelas, making up about 8% of the nation’s population, which reached 215.3 million in 2022.

Until the 1990s, high crime rates in peripheral regions marked and stigmatized the poor and racialized residents of favelas. However, residents began developing their own solutions to combat violence and poverty. This period saw the rise of evangelicalism, an increase in artistic collectives, the proliferation of NGOs, and a stronger state presence, particularly during the first term of President Luís Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2011), known for expanding social rights and consumption.

These social changes led to what Brazilian sociologist Tiaraju D’Andrea calls the “peripheral subjects,” a sense of pride among favela residents. This concept describes individuals who, aware of their vulnerable conditions and overcoming stigma, engage in political actions to transform their reality.

But poverty in Brazil has layers that no AI can fully capture. Despite the proud favela residents and the emergence of a new middle class in Brazil, the country also deals with homelessness.

In 2023, Brazil’s Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship published a report on the country’s homeless population as part of the research conducted to support the “National Policy for the Homeless Population.” The report revealed that 236,400 people were registered as homeless in the federal government’s official records (but other research indicates the actual number exceeds 281,400).

{Note: In Brazilian Portuguese, the word “homeless” does not accurately translate the expressions we use. For example, we no longer use the term “morador de rua” (street resident), which implies an unchangeable condition. Instead, we use “pessoa em situação de rua” (person experiencing life on the street), emphasizing that homelessness is a condition that should be temporary.}

Since landing in Phoenix, we have had many opportunities to explore the downtown area, and I could not stop thinking about homelessness as a global issue. It is not just a problem faced by emerging countries like those my SUSI colleagues and I come from, as I once thought, influenced by many (positive?) stereotypes.

As reported by The New York Times, “the number of unsheltered Phoenix residents has risen dramatically, from 771 in 2014 to 3,096 in 2022, according to the city”. In 2023, the Department of Housing and Urban Development reported 653,104 homeless Americans. The demographics show that most are male (60.5%), adults aged 35 to 44 (20%), and white (49.7%). This mirrors Brazil’s situation: most homeless individuals are male (87%), adults aged 30 to 49 (55%), and Black.

This is definitely not a “stereotypical image of an American.” But after many walks to the supermarket near Gordon Commons and the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, SUSI Scholars were already reflecting on the homelessness situation in Phoenix.

So, the opportunity to volunteer at the Society of St. Vincent de Paul this Saturday (June 15th) came just in time. Upon arrival, we were tagged with our names on a sticker that read “Feed. Clothe. House. Heal.” These words were displayed everywhere, at the reception desk and in the kitchen, summarizing the mission of the Society: “feeding, clothing, housing, and healing individuals and families in our community who have nowhere else to turn for help.”

St. Vincent de Paul is “a community joined by faithful action and pursuit of the common good.” They initiated their activities in Central and Northern Arizona in 1946, offering housing and shelter assistance and meal distribution, serving an impressive 7,000 meals daily (including breakfast, lunch, and dinner).

SUSI Scholars volunteered for various tasks, from chopping vegetables to packaging food, from opening cans to cleaning the floor.

Considering the homeless situation in Phoenix is seen as a “public nuisance,” a one-day volunteering effort might seem insignificant. However, we all left the kitchen feeling that we could accomplish great things as a team… even if it was “just” cutting onions, peppers, and tomatoes, achieving the surprisingly and enthusiastic amount needed for almost three days of meal preparation at St. Vincent de Paul!

I am now just wondering what the “stereotypical” images of teamwork generated by AI might look like. For me, it would be the following:

Good job, SUSIs!