A few years back, I noticed that my journalism students were not well-informed about the prominent news being disseminated through Brazilian TV or online media outlets. I realized that while some were knowledgeable about their favorite sports, reality shows like Big Brother, or the latest gossip surrounding celebrities and YouTubers, they remained oblivious to significant issues within their own city. They were missing out on situations such as the chaotic public transportation scenario, the attacks on Brazil’s schools and the frequent clashes between drug dealers, militia and the police in Rio de Janeiro.

This led me to question the sources they were exploring on the web. It became clear that each student had their favored media platform, presenting a significant challenge for journalism and journalism education. How can faculty help these students break free from the isolated bubbles? How can we empower them to think holistically, providing them with context and equipping them with the skills to think critically and express themselves cohesively? Many of them struggle with constructing well-reasoned arguments, employing logical thinking, maintaining coherence, paying attention to detail, and sustaining concentration and focus.

Then, I introduced a simple activity at the beginning of each class: sharing what was the news within their respective media bubble. This interactive and dynamic exercise encourages greater participation from the students. Over time, they began bringing in more and more news to share with their peers, effectively dismantling their isolated bubbles. Through this process, they understood how challenging the communication field is in today’s world. During these classes, we often found ourselves tracing the journey of a rumour as it transformed into news, or witnessed the birth of fake news.

Furthermore, WhatsApp is the main platform for disseminating disinformation and misinformation in Brazil. This widely popular app has largely replaced traditional phone calls as the preferred means of communication, exacerbating the problem. Due to the end-to-end encryption feature of the messaging service, disinformation and misinformation circulate freely within it. Although Meta, its parent company, has implemented some measures like limiting the number of recipients for a message to restrain mass spamming of messages and fake news, such as the 2018 Brazilian presidential elections or the rampant sharing of messages regarding school attacks in Brazil, WhatsApp remains a challenge in the fight against mis/disinformation.

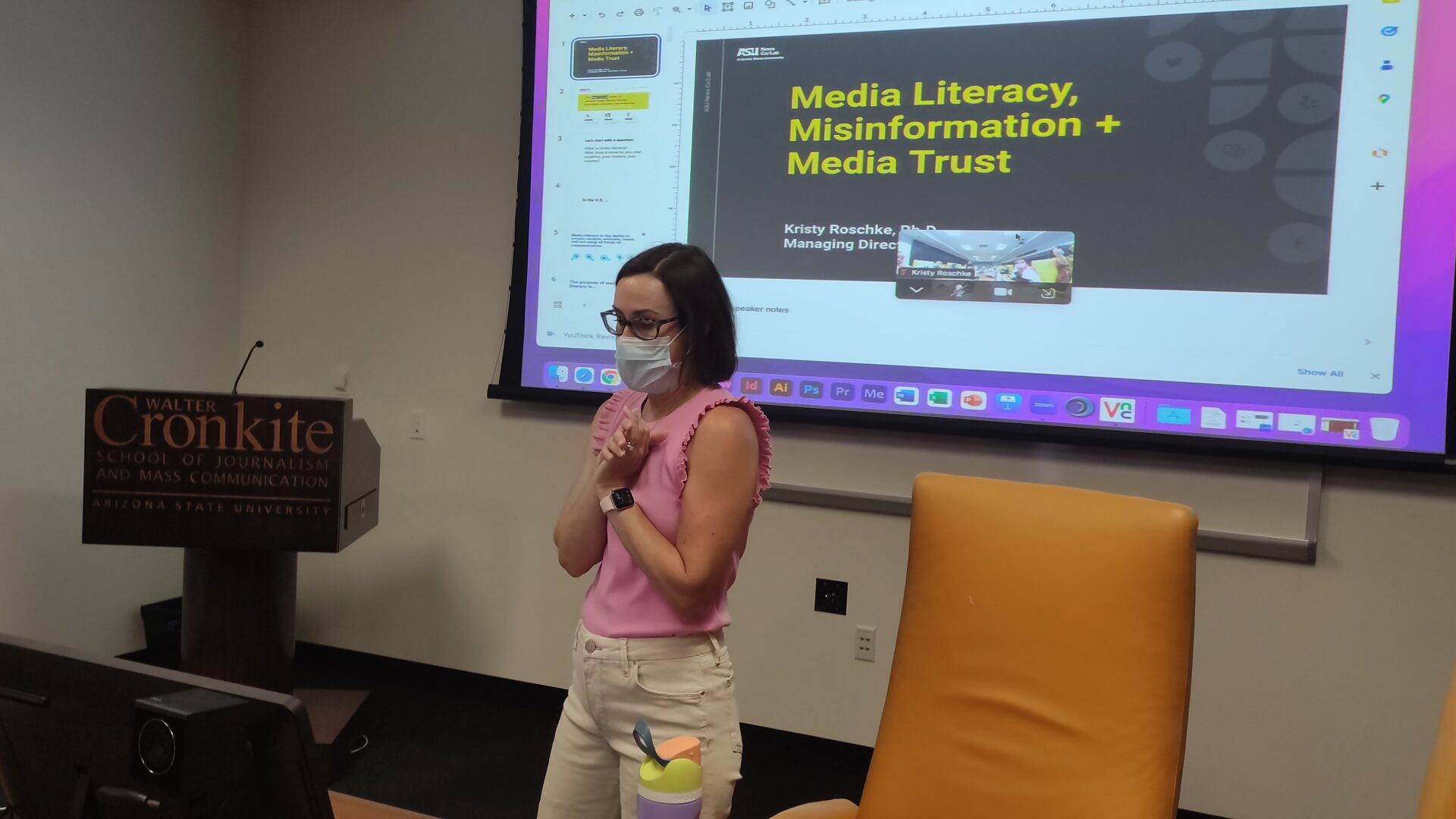

This Monday, the SUSI scholars had a special appointment in room 444 with Dr. Kristy Roschke, Managing Director at ASU News Co/Lab, to discuss media literacy definitions, misinformation and media trust. The goal was to discover common themes and key differences in how we approach these issues in research and practice. Before this meeting, to learn a little more about misinformation and disinformation mechanisms in other countries and gain insights into the challenges of media literacy in journalism education, I reached out to my SUSI classmates via WhatsApp, asking the following questions:

What’s the news in your media bubble today?

Yesterday, the passing of Silvio Berlusconi, former Italian Prime Minister and media tycoon, provoked a series of responses in Brazil as well as other countries in South America and Central America, as per replies by my classmates Angela Van Der Kooye (Suriname) and Alejandro Vargas Johansson (Costa Rica). Meanwhile, in the Western Balkans, Anida Sokol (Bosnia and Herzegovina) told me that in her media bubble it was a prominent video by Dario Kordić, a convicted war criminal who said he would repeat all his crimes again. In Sokhen Sun’s media bubble (Cambodia), the main news was an order from Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen to amend laws in order to remove the right to stand as a candidate at elections for any individual who does not vote. In Firly Annisa’s bubble (Indonesia), the most commented topic was the four Colombian children who survived 40 days in the Amazon jungle after their plane crashed.

What is the main way disinformation spreads in your country?

Based on my classmates’ WhatsApp replies and in the discussion in room 444, it was possible to observe that social media platforms such as Facebook and TikTok, and messaging apps like WhatsApp, Telegram, and the Japanese Line are the main channels through which disinformation proliferates. It is interesting to note that despite the different definitions of misinformation and disinformation in many countries, the term disinformation is more commonly used. According to the First Draft definition, misinformation is unintentional mistakes such as inaccurate photos, captions, dates, statistics, translation or when satire is taken seriously. However, during the discussion with my classmates about the misinformation concept, we found it difficult to define the intentions behind who is sending the message.

What media literacy initiatives do you use with your students?

SUSI scholars spoke about the younger audience’s relationship with their sources of information and the level of trust in institutions and traditional media, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. Some classmates highlighted the need to stimulate students’ critical thinking.

“I teach my students critical thinking because we have much fake news in our country. It’s so bad that it’s turning into a social issue now. The media is used as a propaganda tool in my country, and it has been going on for centuries.”

Angela Van Der Kooye

Similarly, Peter Kravcak (Slovak Republic) said that he tries to discuss with his students what happened, what the consequences were and the impact of the news. Anida shared via WhatsApp that in Bosnia-Herzegovina, there are media literacy initiatives where students learn about disinformation, propaganda and journalistic ethical standards. They also employ a debating format in which the students are divided into for and against groups, and they must follow the rules supporting or opposing a specific topic. According to Sokhen Sun, in Cambodia, there are several measures implemented by local NGOs to improve media literacy in the country. For instance, Campus Media 101, a course where trainees learn about types of fake news, news writing and digital safety.

In conclusion, from our chats on WhatsApp and in room 444, we agree that when it comes to media literacy, disinformation and media trust, our challenges are many and similar in a wide variety of political, social and cultural contexts. The problems are not exactly new, but they have become more complex with digitalization; media literacy is not the only solution to the problems, but it may give some directions.