The stained-glass window that stands in the rear center of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham is distinct from all the others in that venue. Deep shades of blue encircle a stylized figure of a black crucified Christ, which appears to be delicately balanced against the frame. The right hand holds one top corner and the left hand opens up to the other. The right one appears to be making a stop sign – “No more oppression,” the guide told us – whilst the other faces the congregation, open, as a bridge to reconciliation.

This piece of art, designed by John Petts, was a gift by the people of Wales in 1965. Some two years earlier, the Church – which was already a focus point for many of the Civil Rights marches and demonstrations, under the guidance of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth – would become known all over the world. On Sunday, September 15th, 1963, at 10:22 a.m., a bomb exploded just outside the building, killing four young girls attending Sunday School and injuring more than 20 other people. Later that same day, in different parts of Birmingham, an African American youth would be killed by police and one other would be murdered by a mob of white men.

The tragedy would later be mentioned as a turning point in the Civil Rights movement and Wales’ contribution was just one of many that helped the community.

SUSI scholars visited the Church at length, taking their time to appreciate not only the historic value of this National Historic Landmark but also its permanent attachment to the daily life of the city.

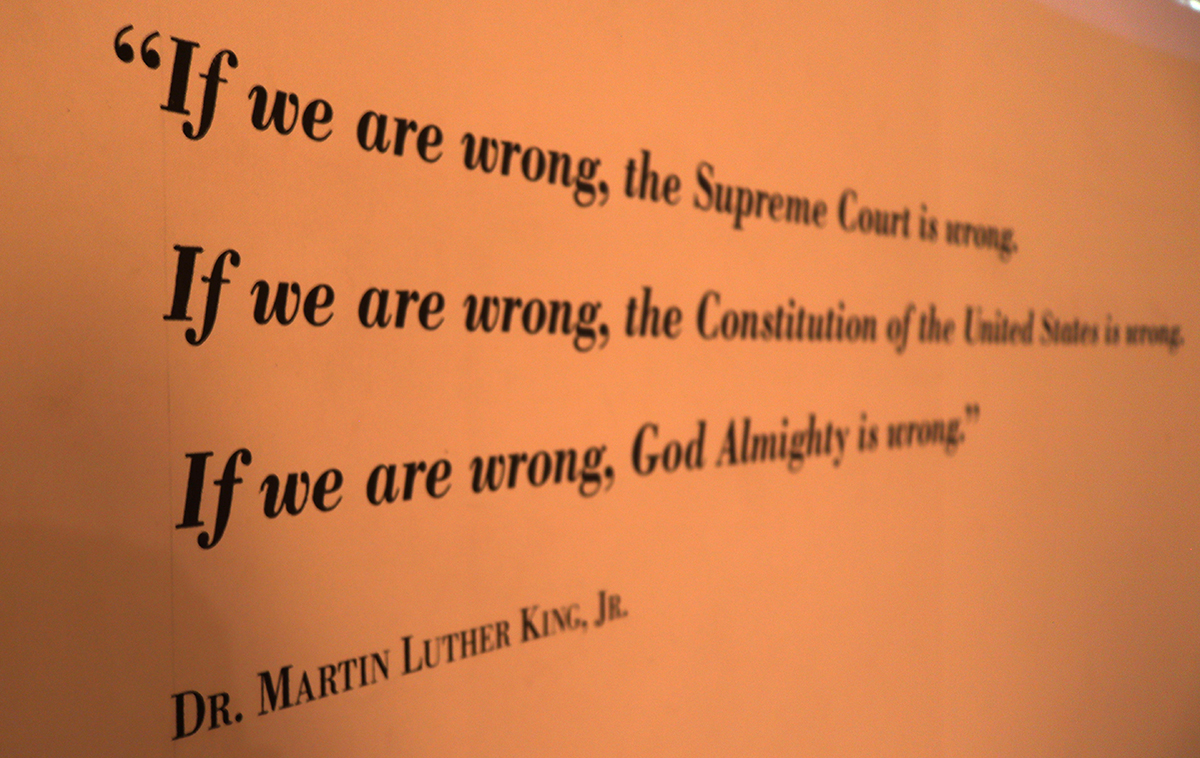

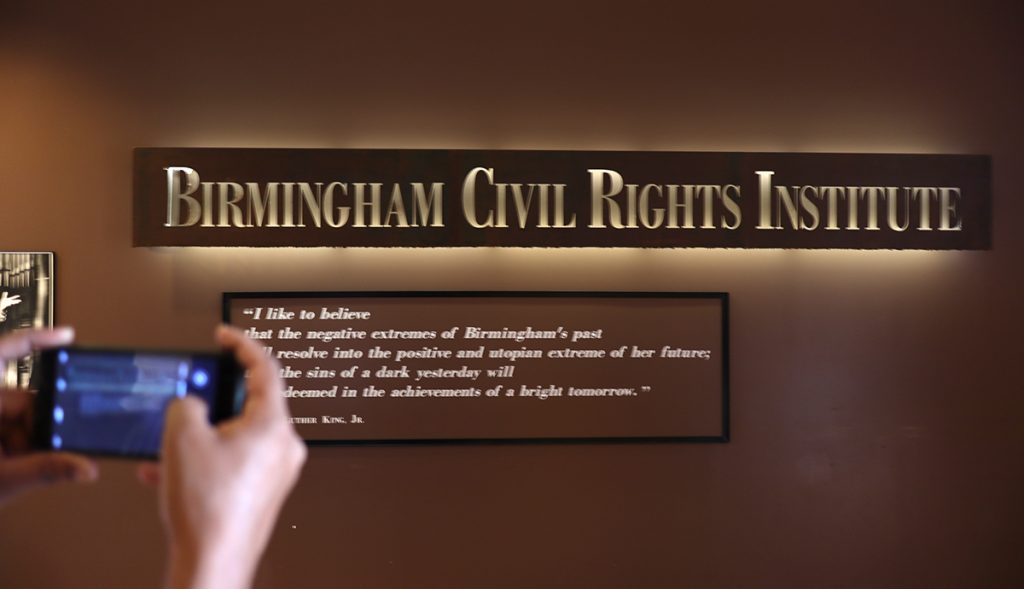

Kelly Ingram Park, just across the street, where in May 1963 more than 1000 demonstrators were confronted by police with dogs and powerful high-pressure water cannons, was also the object of attention on this penultimate Friday of the program just before heading towards the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. This museum houses a series of multimedia exhibitions focusing on the struggle for civil rights and the effects of segregation on African Americans.

More than 50 years have passed since the events portrayed in the exhibitions but some of the yearnings and promises have not yet been fulfilled. As such, John Petts’ image is still as relevant as it was in 1965, offering us a clear roadmap for a better future – pushing oppression and offering reconciliation.